Up, up and away in my beautiful, my beautiful balloon… So the song goes, but what’s it actually like way up high in the atmosphere? Could we humans live up there if we wanted to, or had to? I recall David Attenborough doing a great documentary in the series “The Living Planet” (“The Sky Above” episode, BBC) where he ascended beneath a very large hot-air balloon, complete with oxygen mask and equipment for sampling for life specimens. It was surprising to discover that small insects could be whisked up there and freeze, before descending again and reviving. In this post, let’s take a closer look at what the atmosphere is like above New Zealand. The outer limit of our weather: 10 km above sea level This is the cruising height for large jet aircraft, and the top of Mount Everest almost reaches this height. All clouds at this altitude are frozen (that is, they are made up of ice crystals). Clouds composed of ice crystals have a wispy appearance and are known as cirrus. The tropopause, which marks the top of the troposphere, occurs at about this height. The winds are usually very strong at this level.

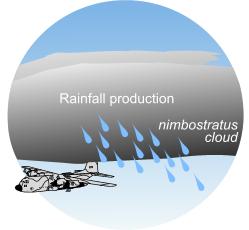

Air pressure: 250 hPa, one quarter of what we experience at the Earth’s surface Temperature: about -55 °C (perhaps on a long-haul flight you've noted on an in-flight air show similar outside temperatures) Air density: 400 grams per cubic metre of air Amount of water vapour: a tenth of a gram of vapour for every kilogram of air The middle levels: 5 km above sea level Most of our rainfall is produced in clouds at around this level, where there are often large regions of rising air currents. The deep rainy clouds are nimbostratus, and other shallower types are altostratus and altocumulus. Rain or hail can fall from cumulonimbus clouds, where the air rises strongly but over a smaller area. Clouds may or may not be frozen - they may be composed of ice crystals or super-cooled water droplets (liquid water at temperatures below freezing). Smaller passenger aircraft connecting cities within NZ often fly at around this altitude. At this height there's less oxygen in the air, but people in some parts of the world. e.g. Tibet and the Andes, are still able to live in these conditions.

Air pressure: about 500 hPa, half of what we experience at the Earth’s surface Temperature: about -25 to -15 °C Air density: 700 grams per cubic metre of air Amount of water vapour: 1 gram of vapour per kilogram of air The lower levels: 3 km above sea level The middle-level clouds can extend down to this level. Large cumulus can bubble upwards to this level too. Because NZ is mountainous, the clouds are often shaped by the air as it flows over the mountains. Clouds are generally not frozen (that is, they are made up of liquid water). Mount Cook rises to just above this level.

Air pressure: about 700 hPa Temperature: variable, but usually between -10 and +5 °C Air density: 900 grams per cubic metre of air Amount of water vapour: from 1 to 5 grams of vapour per kilogram of air The Earth’s surface: close to sea level  Air pressure: typically between 980 and 1030 hPa (sometimes there are extremes outside this) Temperature: highly variable, usually between 0 and 30 °C (extreme highs are often due to the Foehn wind) Air density: 1.2 kilograms per cubic metre of air Amount of water vapour: highly variable, from 5 to 15 grams of vapour per kilogram of air. The illustration shows two common types of low altitude clouds. You can see more pictures of these and other cloud types in the MetService cloud poster. You may be wondering what lies above the tropopause. Above this level you’d enter the stratosphere. To give you an idea, at 15 km above sea level the air pressure is about 100 hPa, temperature interestingly remains fairly steady at about -60 °C, and the water vapour content is negligible. Within the stratosphere is the ozone layer which, fortunately for us, absorbs most of the harmful ultraviolet light from the sun. By the way, note the similarity in the words "stratosphere" and "stratus". Both originate from the Latin word for "layer" - the stratosphere is resistant to vertical motion so tends to have a layered structure, and stratus cloud has a somewhat layered appearance. So far I’ve confined this post to NZ. Towards the tropics the temperature obviously rises, but it’s a little known paradox that the coldest of all tropospheric temperatures are in the tropics at about the altitude of the tropopause there (around -80 °C). I think it’s interesting to compare the conditions at the surface with which we’re familiar, with those higher up. At what altitude do you think you could still function? Going up, up and away in a beautiful balloon is a wonderful thought, but make sure you go prepared for the conditions!

Air pressure: typically between 980 and 1030 hPa (sometimes there are extremes outside this) Temperature: highly variable, usually between 0 and 30 °C (extreme highs are often due to the Foehn wind) Air density: 1.2 kilograms per cubic metre of air Amount of water vapour: highly variable, from 5 to 15 grams of vapour per kilogram of air. The illustration shows two common types of low altitude clouds. You can see more pictures of these and other cloud types in the MetService cloud poster. You may be wondering what lies above the tropopause. Above this level you’d enter the stratosphere. To give you an idea, at 15 km above sea level the air pressure is about 100 hPa, temperature interestingly remains fairly steady at about -60 °C, and the water vapour content is negligible. Within the stratosphere is the ozone layer which, fortunately for us, absorbs most of the harmful ultraviolet light from the sun. By the way, note the similarity in the words "stratosphere" and "stratus". Both originate from the Latin word for "layer" - the stratosphere is resistant to vertical motion so tends to have a layered structure, and stratus cloud has a somewhat layered appearance. So far I’ve confined this post to NZ. Towards the tropics the temperature obviously rises, but it’s a little known paradox that the coldest of all tropospheric temperatures are in the tropics at about the altitude of the tropopause there (around -80 °C). I think it’s interesting to compare the conditions at the surface with which we’re familiar, with those higher up. At what altitude do you think you could still function? Going up, up and away in a beautiful balloon is a wonderful thought, but make sure you go prepared for the conditions!