In my previous blog post I pointed out that tropical lows and cyclones don't have fronts like the lows we're used to around NZ, but rather, a core of warm air near the centre. I'd like to follow up by further contrasting tropical and mid-latitude lows, and looking a bit more closely at tropical cyclones and how they can affect our weather in New Zealand.

When tropical lows fully develop into cyclones they become the most damaging of tropical weather features. There are three main reasons for this:

-

damaging winds at, or very close to the Earth's surface

-

intense rainfall leading to flooding

-

near the coasts, the sea can be driven inland as a storm surge.

In an earlier blog post we saw that, on a weather map, the closeness of the isobars is related to the strength of the wind. There is a latitude effect too: for a given isobar spacing, if you were nearer the equator the wind would be stronger than if you were nearer the poles. This is an important point, because a tropical cyclone has very closely packed isobars near its centre and is relatively close to the equator.

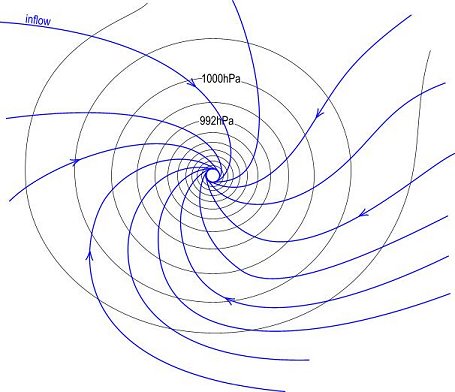

Also, as you get nearer the equator the wind blows more across isobars, in contrast to the mid-latitudes where the wind blows approximately parallel with the isobars (like slot cars on a track). So in tropical cyclones there is a strong inflow into the centre as in the diagram below.

Inflow into a tropical cyclone (southern hemisphere). The innermost circle represents the "eye".

Inflow into a tropical cyclone (southern hemisphere). The innermost circle represents the "eye".

I don't want to overcomplicate things, but there is a further effect based on the curvature of the isobars. If you're interested send me a comment and I'll explain it.

At the innermost circle in the diagram, the air is racing so fast that it doesn't make it all the way into the centre. Inside this circle is the eye and a phenomenal contrast between the wind and rain at the outer wall and the relative calm of the interior. The rainfall is usually at its most intense just outside the eye, and the cloud is very deep with extremely cold tops - see for example the infra-red satellite pictures described in the previous post.

I remember being in Darwin many years ago when Cyclone Rachel was over the Timor Sea. We were some distance away from the centre of Rachel, but the cloud overhead was so dense that we needed lights on during the daytime if we wanted to read. We set a 24hr rainfall record for Darwin of 290mm, although the wind wasn't particularly strong (compared with what I'm used to in Wellington).

Tropical cyclones sometimes affect New Zealand during our warmer months - a couple of examples were mentioned here. You may well recall some more recent examples, e.g. Drena and Fergus. After they form in the tropics they typically move quite slowly and erratically, then usually curve southeastwards into the mid-latitudes.

Once they move over colder water in mid-latitudes they undergo a transition in structure from the tropical to the extra-tropical (meaning outside the tropics, like "extraordinary" means "outside the ordinary").

At this stage the cyclone tends to expand by drawing in colder contrasting air and evolving into a more typical mid-latitude storm complete with warm and cold fronts. On a few occasions (e.g. the Wahine Storm in 1968) they interact with a vigorous mid-latitude low to form a new system, complete with active fronts. Either way, the new storm isn't a tropical cyclone anymore in terms of structure but can still be very damaging as a major mid-latitude depression.