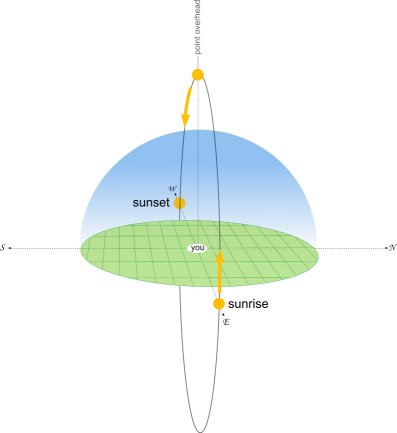

As we approach summer in NZ, the Sun gets higher in the sky and increasingly warms the Earth and the air around us. In the early 1600s Galileo Galilei explained that the Earth goes around the Sun, but there's no reason why we can't discuss the apparent movement of the Sun across the sky, as you see it from a frame of reference fixed to the Earth. Let's do that, and investigate the different ways that the Sun drives our seasons. On the 21st or 22nd December in New Zealand we hit the summer solstice. The movement of the Sun across the sky on that date is like this:

How the Sun moves over NZ on the Summer Solstice. Note how it rises and sets south of east and west.

If your house has a south-facing wall you may notice that it gets some direct sunlight in the early morning or late evening at this time of year. You can compute how high the Sun gets in the sky at your place by first letting the point directly over your head be 90° angle above your horizon. I'll explain what happens at an equinox, then I'll go into the solstice computation.

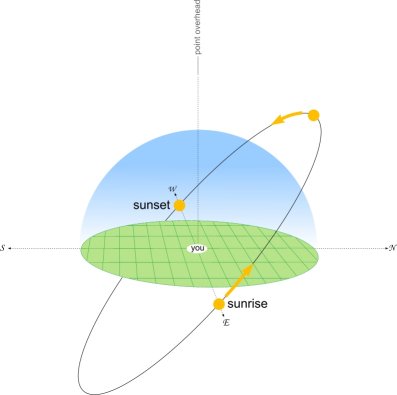

• At the equinoxes On March 21st or 22nd in New Zealand, and also 23rd September, the Sun is directly overhead the equator. At your place the Sun reaches a maximum angle of 90° minus your latitude. For example, the latitude of North Island is approximately 40°S (you can be more precise for your location by looking at an atlas). So, at an equinox, the Sun reaches a maximum elevation angle of 50° above the horizon.

How the Sun moves over NZ on the Spring and Autumnal Equinoxes. It rises exactly in the east, and sets exactly in the west.

• At the solstices At the December solstice the Sun has moved to its southernmost point, directly overhead latitude 23.5°S, called Tropic of Capricorn. E.g. at Rockhampton the Sun will reach 90° directly overhead around midday on the Summer Solstice. Over North Island, the elevation of the Sun increases to a maximum of 50° plus the 23.5° (the tilt of the Earth's axis), i.e. 73.5°, as shown in the animation at the start of this post. That's pretty high in the sky. In the middle of a sunny day near the Summer Solstice, you will notice how short your shadow is due to the high angle of the sun. In the depths of winter over North Island the Sun only reaches 50° - 23.5° = 26.5° above the horizon (see the animation below), which is not very high :-( Roll on summer.

For interest, if you have been to the tropics, you may have noticed that the duration of sunset is short as the Sun sinks almost straight down below the horizon. It's a similar story for sunrise. The next diagram shows how the Sun moves on the equator.

At the South Pole, the Sun moves parallel with the horizon, always keeping the same elevation, as shown below. Nearer the Antarctic coast, e.g. at Scott Base, the Sun rises very gradually. Even on the Summer Solstice it doesn't get very high in the sky there (about 35° max) and, in winter, the Sun doesn't even make it above the horizon as it goes around.

To protect our eyes we never look directly at the Sun. But, as I alluded earlier, we can infer the Sun's position from the shadows it casts. I remember Augie Auer quoted a rough rule of thumb, that if your shadow is shorter than your height you should be protecting yourself from the sun. In other words, if the Sun is higher than 45° elevation, you are more likely to get sunburn. I hope this post has given you a better understanding of why we get these higher Sun elevations in the summer months. You can check out detailed data such as sunrise/sunset times at your place, Sun angle and lots more besides, at the US Naval Observatory website.