April 2010

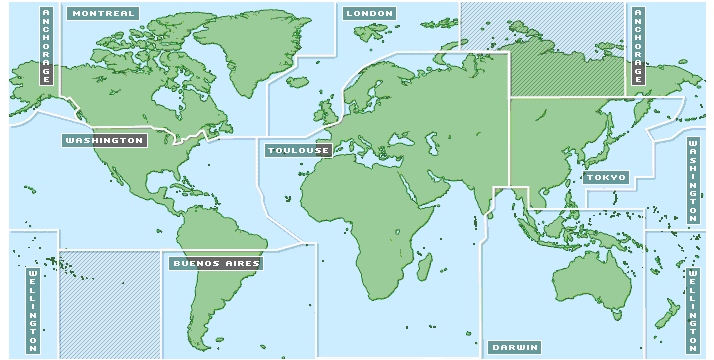

MetService provides a Volcanic Ash Advisory Service (VAAS) as one of nine global Volcanic Ash Advisory Centres (VAACs). MetService aviation forecasters in Wellington issue ash warnings for a large part of the South Pacific, from the South Pole to the equator and from halfway across the Tasman Sea to more than halfway to Chile.

Click on the map below to visit the VAAC

The VAAS is part of an international system set up by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) called the International Airways Volcano Watch (IAVW). The IAVW comprises observations of volcanic ash from volcano observatories and other organisations, satellites and aircraft in flight, the issue of warnings in the form of NOTAM and SIGMET messages and, since the mid 1990s, the issue of volcanic ash advisory messages from the Volcanic Ash Advisory Centres identifying areas of volcanic ash and their predicted movement.

The IAVW was established in the wake of the flight of Speedbird 9 through ash from Galunggung in 1982. The Captain, Eric Moody, made the memorable announcement “Ladies and gentlemen, this is your captain speaking. We have a small problem. All four engines have stopped. We are doing our damnedest to get them under control. I trust you are not in too much distress.”

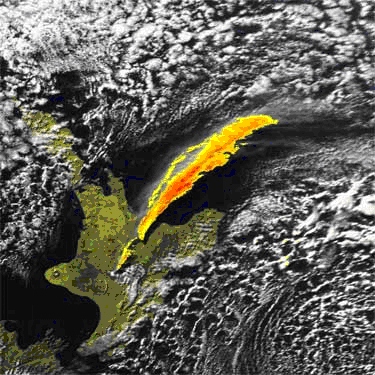

During the mid 90s Mt Ruapehu had a series of eruptions and New Zealand’s Civil Aviation Authority CAA operated a Volcanic Ash Watch Office, using MetService to help track the ash emissions. Subsequently the VAAS was established. Over recent years, improvements in observation networks, satellite technology, computer modelling and our increased understanding of the phenomena have led to improved volcanic ash forecasting methods.

Ash plume from Mt. Ruapehu, 17 June 1996: photo from NASA and at Te Ara encyclopedia.

Ash plume from Mt. Ruapehu, 17 June 1996: photo from NASA and at Te Ara encyclopedia.

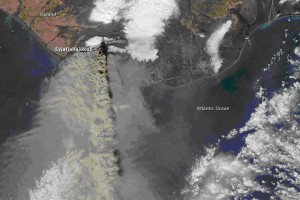

Iceland’s Eyjafjallajokull volcano’s eruption, combined with shifting upper winds, have been taking ash clouds across Europe, affecting international aviation. See for example this image from NASA Earth Observatory .

Volcanic ash is an aviation hazard. Fine, corrosive and abrasive, ash can coat aircraft wings, block speed sensors and air filters, sandblast flight-deck windscreens and aircraft lights, and form glass-like coatings inside engines that damage moving parts and can cause engine failure. Such potentially serious and expensive damage is best prevented by avoiding flying through ash altogether.

The size and cost of the disruption caused by the recent volcanic ash over the UK and Europe may well prompt strengthened efforts to improve detection and forecasting of ash, as well as new strategies to cope with the risk it poses.