This change-of-colour amongst the trees moves from south to north in tune with decreasing day-length. The intensity and duration of "autumn colour" depends on the weather as we slide slowly into the darker months.

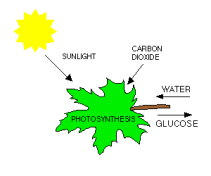

For growth, trees draw on the four basic elements: earth and water (soil moisture), fire and air (sunlight and Carbon Dioxide). During summer the green chlorophyll of leaves takes in water (from rain-fed roots in the earth) and carbon dioxide (from the air) and uses sunlight in the process of photosynthesis to make glucose (sugar) which is used by the tree for food. Chlorophyll appears green because it is a very strong absorber of red and blue light, using this energy for photosynthesis.

Shorter days in autumn are the trigger for cells at the base of the leaf stem (the abscission layer) to swell and cut off the connections between leaf and tree. Grapes and Kiwifruit also shed their leaves this way so that new ones can grow in the spring. Without fresh water to renew it, the chlorophyll in the leaf stops working and starts decaying. As the bright green chlorophyll fades away, glucose and other products that are left behind start to show their colours.

Orange comes from carotene and yellow from xanthophyll; common pigments that are also found in flowers and foods like carrots and egg yolks. These compounds act as accessories for chlorophyll: they cannot do any photosynthesis themselves but they do absorb green light (which is not being used by chlorophyll) and transfer some of this energy to help the chlorophyll.

The bright red and purple colours come from anthocyanin pigments, which are made from any leftover glucose trapped within the leaves of some trees (e.g. maples and some oaks).

These pigments are also found in plants; for example, rhubarb, beets, red apples, and purple grapes, and flowers like violets and hyacinths.

Brown leaf colours come from tannin, a bitter waste product also found in tea leaves.

Each autumn brings a different combination of these pigments and a varying range of colour. The brightest colours are seen when autumn has bright sunny days and cool (but not frosty) nights. Under these conditions leaves can make a lot of sugar as their veins close down, trapping anthocyanin pigments that produce such glorious red and purple hues. Alternatively, if autumn has lots of cloudy days and warm nights then these red pigments are missing and the display is rather drab. An early frost or a strong wind speeds up the fall of the leaves and may bring an early end to the colour of autumn. Soil moisture during summer also has a variable impact on leaf health and hence on autumn colour. Leaves directly exposed to the sun may turn red, while those on the shady side of the same tree or nearby trees may be yellow.

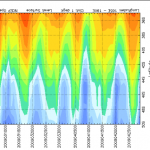

So, how does autumn 2009 measure up for colour? A good way to view temperatures for the past few months is offered in the public domain by the Physical Sciences Division of NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratory. In the first image below a time section is given of the surface air temperature from the latitudes of 35 South (top) to 50 South (bottom). The image covers from March 1st at left to April 30th at right. The daily mean over the longitudes from 165 to 180 East is used, so this image does not show the day/night or west/east variation or the ground frosts. It does show clearly how much Northland (around 36 South) is warmer than Southland (around 46 South), and reveals an almost weekly cycle of warmth and coolness.

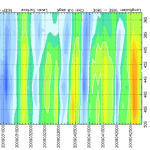

(Above) Left: Time Section of surface air temperature over NZ for March and April 2009.(deg K= dec C +273), Right: Variation from normal (blue is cooler and red is warmer). Click images to enlarge.

Time Section images provided by the NOAA/ESRL Physical Sciences Division, Boulder Colorado from their Web site at http://www.cdc.noaa.gov/

To show the variation from normal, the second image gives the temperature anomaly. This is interesting in that there is more blue than red for most of autumn. We mostly attribute that to cooler-than-normal nights due to clear skies in passing anticyclones. The frostiest morning was 22 April when MetService measured a 7 degree frost at Masterton (grass minimum temperature was -7C). There were a few noticeable cold fronts as well: one on 11 March brought light snow to the Remarkables and another on 9 April, just before Easter, brought 20 cm of snow to Mt. Hutt. Generally the winds have been less than normal this autumn allowing the leaves to stay on the trees longer. The warmth since ANZAC weekend has been more noticeable in the South Island than further north.

During February coastal Hawke's Bay and Gisborne missed out on rain that replenished the soil moisture everywhere else in New Zealand. This is likely to make the timing and brilliance of their autumn colour different from other regions, and maybe noticeably different between hills and coast. I'm not sure what the difference will be, so I'm especially interested in getting replies to this post from people in the eastern North Island. Click here to read more about how weather affects autumn colour.

Thanks to Alan McDougall of MetService's Media Graphics Unit in Christchurch for contributing these photos taken during ANZAC weekend 2009.