Written by Erick Brenstrum, Meteorologist

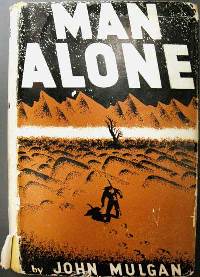

In John Mulgan’s novel Man Alone stormy weather plays a crucial role hiding the hero, Johnson, when he is on the run after accidently killing a man on an isolated farm near Ohakune. Fleeing through the night on horseback, Johnson takes a track up Mount Ruapehu as a southeast storm is building. He is aiming to hide in the wilderness of the Kaimanawa Ranges but cannot reach them before daybreak. After a few hours sleep in a hut near the bush line, he walks around the side of Ruapehu cloaked by rain and mist then drops down a ridge into the tussock country of the Rangipo desert. But the weather that hides him from pursuit also threatens to kill him with cold.

On his first night in the open, he digs a shallow trench into the pumice for partial shelter from the gale. The next day, the wind reaches its peak, becoming so strong it forces Johnson to his knees, blasts him with sand and disorients him. It’s moaning “more mournful and frightening than anything human he had known.” The wind and the rain last the three days it takes Johnson to cross the open country of the central plateau and reach the safety of the Kaimanawa Ranges. He is ill by this time, but recovers in the forest, wintering over in a cave, before emerging on the Hawkes Bay side of the ranges in spring. Eventually Johnson escapes New Zealand by ship and ends up fighting with the International Brigade against Franco’s fascists in the Spanish Civil War.

Weather is often used to add drama to literature. Examples abound from the storms in Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, to Shakespeare’s King Lear raging on the heath or the deadly effects of winter in Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Mulgan was influenced by Hemingway whose famous novel, Farewell to Arms, has two moments when bad weather aids the hero, Frederic Henry, an American serving in the medical core of the Italian Army during the First World War. In the chaotic retreat in the rain after a major defeat the remnants of the army crosses the flooded river Tagliamento. As the crushed mass of soldiers reaches the far side, military police single out officers or suspected enemy agents and execute them for causing the defeat. Doubly suspicious as an officer who speaks Italian with a foreign accent, Henry is seized but breaks free and dives into the river before he can be shot. A few days later, Henry avoids imminent arrest by civilian police, fleeing in the night by rowing down Lake Maggiore to Switzerland, hiding from border patrols in patches of mist and rain.

As a scholar of Latin and Greek, Mulgan was also likely to have been aware of stories of bad weather being used to advantage in ancient warfare. For example, during the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta in the fifth century B.C. the Athenian general Alcibiades risked stormy seas to sail a large fleet undetected through heavy rain at night to close on Spartan positions at Cyzicus. The next morning, Alcibiades sailed forty ships towards the Spartans. Thinking this was all the force at his disposal, the Spartans launched their fleet and pursued Alcibiades as he retreated out to sea. This allowed the bulk of the Athenian fleet that was concealed behind a promontory, to sail behind the Spartans and cut them off from their base. The ensuing battle was a great victory for the Athenians, although it failed to determine the outcome of the war.

An interesting example of author as hero occurs when Julius Caesar was fighting in Gaul in the first century B.C. At the end of each year’s campaign Caesar wrote a history of the fighting and had it circulated in Rome. He could not stray too far from the facts as others in his army were also writing home, but Caesar’s version painted his actions in the best possible light in order to wrong foot his political opponents in Rome. In the siege of the fortified town of Bourges, Caesar writes that he decided to take advantage of a heavy rainstorm to launch his successful assault when the defenders were off guard. In this story Caesar was echoing incidents from Homers Iliad – a work well known to educated Romans – where the gods used weather to intervene in the fighting between the Achaeans and the Trojans, causing a mist to descend over a warrior whom they sought to protect when the fight went against him.

A god wielding the weather as a weapon also decides the outcome of a crucial combat in the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh. The oldest story we know, Gilgamesh was written in cuneiform inscribed on clay tablets more than four thousand years ago and progressively unearthed in fragments by archaeologists over the last two centuries.

In order to fetch timber to repair the temples of his city of Uruk, as well as to gain the immortality of fame and glory, Gilgamesh undertakes a long journey to the mountains where cedar grows. The forest is guarded by the ogre Humbaba, who is protected by deadly auras – “his speech is fire his breath is death.” Gilgamesh triumphs because of the intervention of the sun god Shamash, who unleashes the thirteen storm winds to blind Humbaba.

Mulgan himself went to war, fighting first in the desert at El Alamein and later behind German lines in Greece. His knowledge of the ancient Greek language enabled him to become fluent in Modern Greek so that he earned the reputation as the most effective liaison officer with the Greek Andartes, leading them in numerous attacks on the Germans defending the railway. These were carried out under cover of darkness but, as far as we know, bad weather was not used for deception, although Mulgan did travel cross country in daytime, shielded by rainstorms. With its dangers and opportunities, the weather has been with us since the beginning and we have been hiding in the rain off and on for thousands of years.